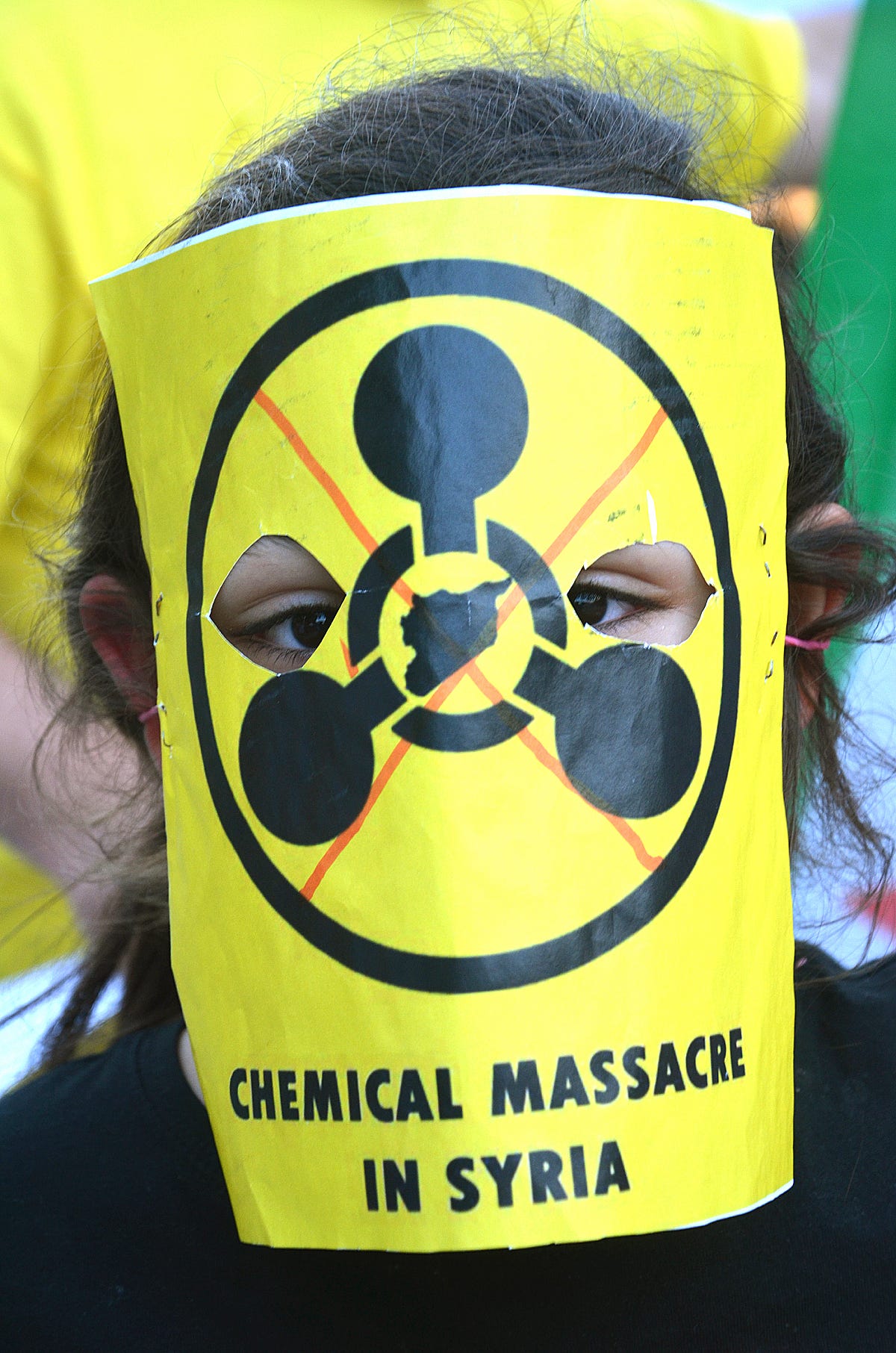

“Ghouta” is a word I grew up hearing. It was one that immediately came to reflect both a eulogy of the dead and an omen for the living in Syria’s revolution. A suburb to the northeast of Damascus, Ghouta was the site of a deadly chemical attack by Syrian government forces in 2013 in which hundreds of civilians were killed. Everything that it entailed - countless deaths, steadfast denialism, de facto impunity, and undaunted repetition - represented everything that was to come during Syria’s civil war. Perhaps that is the most awful thing about it. Even the worst of tragedies are always laced, however thinly, with some kind of meaning, some veneer of historical significance.

The most notable thing about the Ghouta chemical attack was that it was nothing. It became nothing and amounted to nothing – except a series of tepid international calls for justice and a barrage of denial, conspiracy, blame-shifting and nauseating dehumanisation by Bashar al-Assad’s regime and its vociferous supporters (many of whom were also to be found internationally, in the ostensibly “anti-imperialist left”). This was what the Syrian civil war itself became. Atrocity succeeded by apathy succeeded by the atrophy of hope. It was the beginning of the end; when Assad got away with that, he knew, despite the bellowing and the bluster, he would get away with anything. And he did. And he continues to do so.

Even the worst of tragedies are always laced, however thinly, with some kind of meaning, some veneer of historical significance.

This is because Assad learned a very easy trick, very early on. He did not invent it, but he did master it. It is the same trick that Abdel Fattah al-Sisi uses in Egypt. It is expertly applied by Khalifa Haftar in Libya. Benjamin Netanyahu is only the latest in a long line of Israeli leaders to make use of it. The trick is to spend years – perhaps decades – crushing any democratic resistance while simultaneously throwing money at hardline insurgencies: Al-Qaeda and its splinters, regional offshoots of the Muslim Brotherhood, various Islamist militias. Whatever fits the bill. Mix this all together and store it in a tin-can called “leverage”. Stow it away for an inevitably rainy day.

And then, when popular and global pressure begins to bite and your excuses run out, reach for this tin-can and turn to the world with a dichotomy that is both false and impossible to reject: It is me or the insurgents, autocracy or terrorism. It does not matter very much who else is opposing you: it matters little whether they are terrorists or Muslims or whatever else. Assad’s opposition has spanned at one time or another Sunni Muslims in Damascus to Kurds in Afrin to the Druze in Suweyda to Palestinians in Yarmouk. But the dichotomy – a secular government against a tide of bloodthirsty Islamists – is so striking it blurs all nuances and softens all criticisms.

This well-constructed bogeyman – the lurking militant poised to unseat the orderly statesman – takes on a gravitas of its own. Your critics will rush to your defence. Bodies will be eaten through by gas and their memory swallowed up by disinformation, a sickly double killing. Not only are hundreds of thousands murdered but they die violently ejected from their own existence – as terrorists, as thugs, as vermin.

As their corpses rot, the flies of some faraway vitriol pick at their humanity – for whom did they fight, or for what, and from where. These diatribes steer public discourse for some time, trying to determine who merits grief. While this vapid racket drones on, autocrats like Mr. Assad have but one task: wipe your hands, take a seat and wait it out. It may be months, perhaps even years, but time will pass, compassion for the dead dwindle, and empathies for the displaced disperse. The bodies will be swept aside and the carpet rolled out and you will be welcomed back into the fold once more.

All Arabs in resistance are told to prime their victimhood just so: to lie still, to play dead, to rot quietly.

After President Assad choked 1,500 of his citizens to death in 2013, he learned he could do anything. He could deploy indiscriminate shelling and cluster bombs; he could besiege cities and bury vital humanitarian aid underground; he could bring in Russian warplanes and Iranian militias; he could starve a country out and barricade the world from feeding them. 90% of the 336 chemical attacks committed by the Assad regime took place after Ghouta — in other words, after Assad glanced over at the green light of international passivity and winked.

All Arabs in resistance are told to prime their victimhood just so: to lie still, to play dead, to rot quietly. They are told that if they do this, help will come. This is a lie. No one is coming to save you; no one is applauding your restraint. There are no awards for quietude in death. If I took one immutable lesson from Ghouta, it is that no one else is going to do your justice for you.

Many trying to advocate for freedom in Syria, Palestine, Egypt, or elsewhere fear being branded a terrorist. The unfortunate truth is that their opponents are taking nothing from this reticence but impunity. So you might as well fight back.